Network communication uses protocols, switching, and routing to move data between devices. Addresses data flow, packet handling, and traffic paths in networks.

A network connects devices to exchange data reliably through standardized communication methods. Every time a computer sends an email, streams video, or accesses a shared file, protocols govern how that information travels from source to destination. The physical infrastructure handles the actual transmission, but switching and routing determine the path each data packet takes through interconnected systems.

Modern networks range from small office setups with a handful of devices to global infrastructures spanning continents. Understanding how these systems operate provides the foundation for designing reliable, scalable connectivity solutions. Whether troubleshooting a slow connection or planning enterprise architecture, the same core principles apply.

What Are Network Fundamentals and How Networks Operate

At its core, a network is a collection of interconnected devices exchanging data. The scale of this interconnection serves as the primary means of classification. A Local Area Network covers a single building or campus. A Wide Area Network spans large geographical distances, connecting separate LANs across cities or continents. A Metropolitan Area Network operates on a city-wide scale.

Devices interact using one of two primary architectural models. In the Client-Server model, a central server provides resources to multiple client devices. This architecture offers centralized management but creates a potential single point of failure. The Peer-to-Peer model allows direct resource sharing between devices acting as both clients and servers.

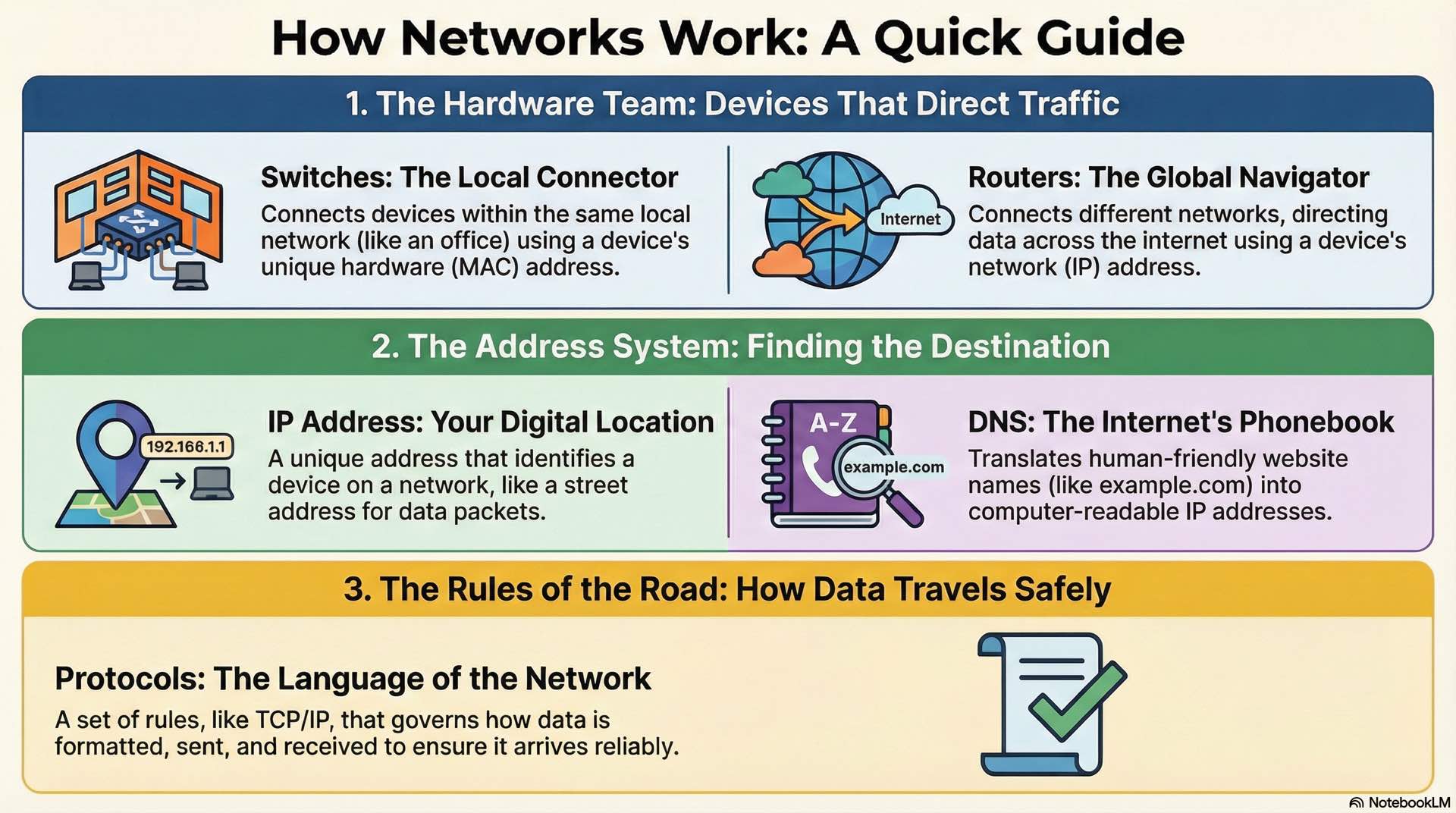

The industry relies on conceptual frameworks like the OSI and TCP/IP models for interoperability. The Physical Layer governs raw transmission of bits over hardware. The Data Link Layer uses MAC addresses to manage hop-by-hop delivery on each local segment. The Network Layer uses logical IP addresses to determine the end-to-end path across different networks.

What Are Network Topologies and How They Affect Design

Bus, star, ring, and mesh topologies

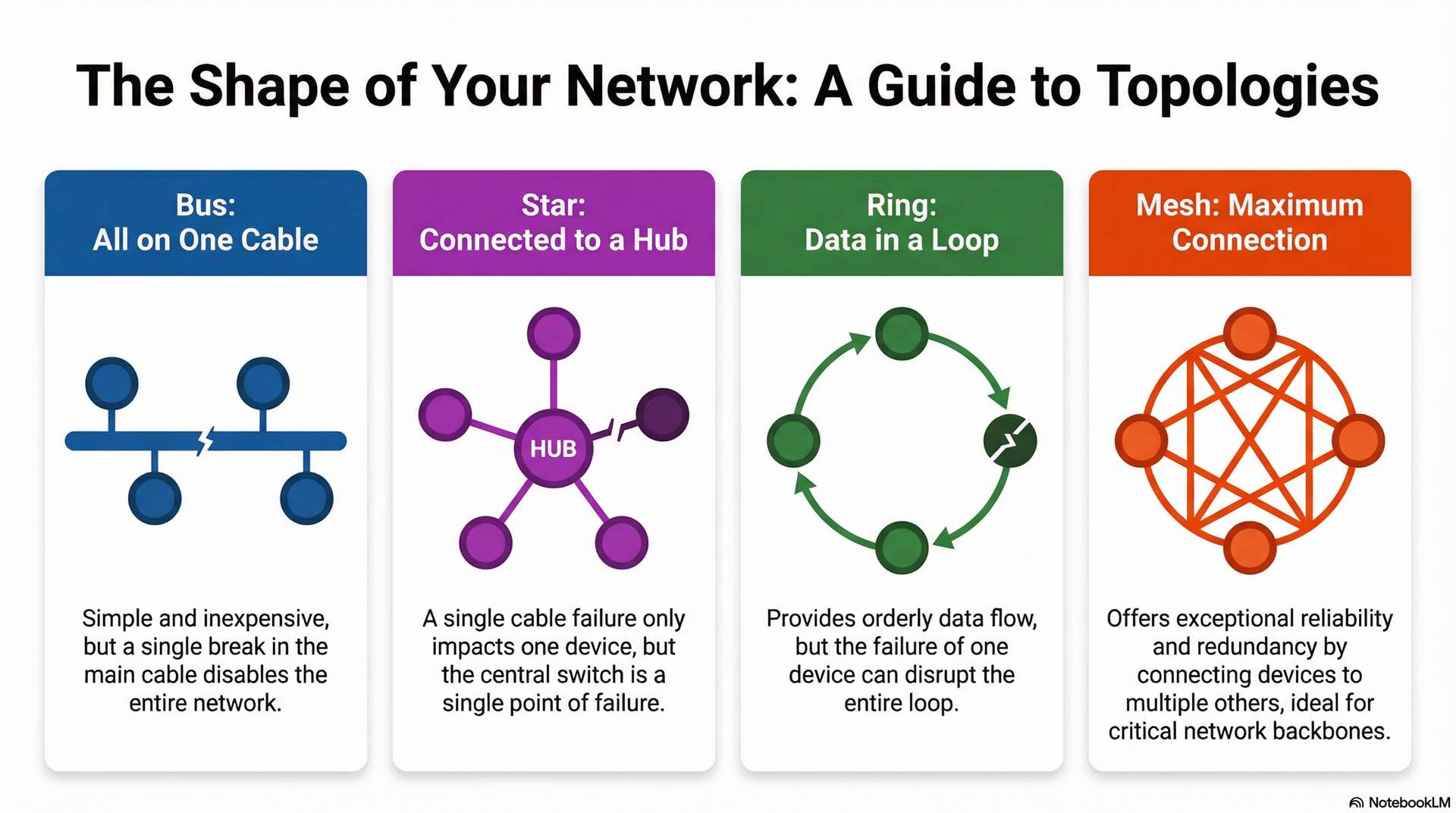

The physical layout of a network determines its performance characteristics and failure modes. A bus topology connects all devices to a single central cable. While simple and inexpensive, a break in the main cable disables the entire network. Legacy coaxial Ethernet networks used this design.

Star topology connects devices to a central switch. This design simplifies troubleshooting since a single cable failure only impacts one device. However, the central device represents a potential single point of failure. Most modern office LANs use star configurations.

Ring topology arranges devices in a circular loop where data passes sequentially from one device to the next. Token Ring networks used this approach, offering orderly communication but vulnerability to single-node failures.

Mesh topology provides exceptional redundancy by connecting every device to every other device in a full mesh, or to multiple devices in a partial mesh. Core network backbones typically use mesh designs where reliability justifies the cost.

Hybrid and high-availability designs

Production networks rarely use pure topologies. Hybrid designs combine multiple topology elements to leverage their respective strengths. A common enterprise approach uses a mesh core connecting distribution switches, with star configurations extending to end-user access layers.

High-availability architectures incorporate redundant paths and automatic failover mechanisms. Dual-homed servers connect to multiple switches. Redundant uplinks connect access to distribution layers.

Spanning Tree Protocol prevents network loops by blocking redundant paths until they’re needed for failover.

Network Devices and Components Used in Data Communication

End devices and network interfaces

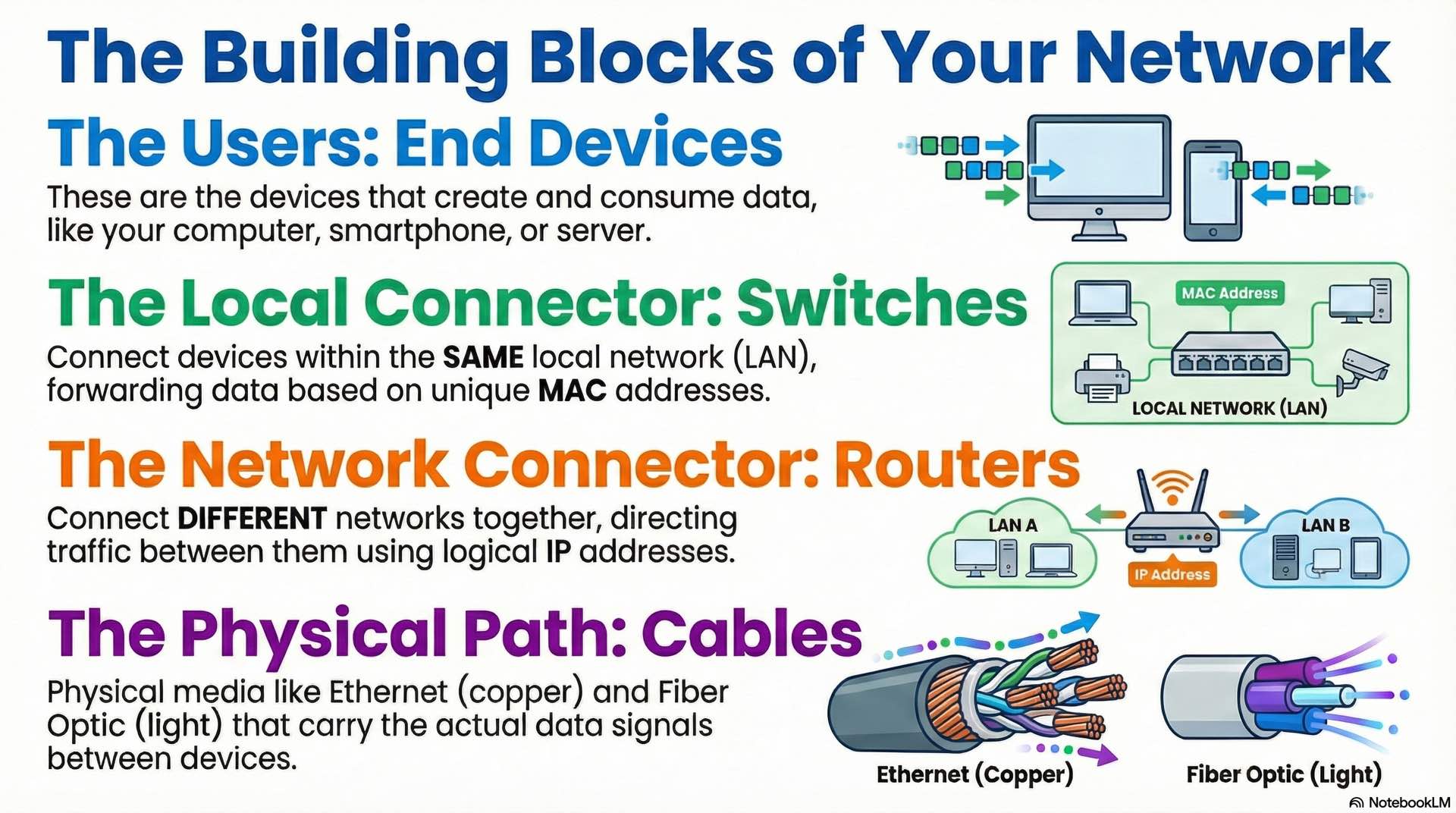

End devices generate and consume network traffic. Computers, smartphones, servers, IP cameras, and IoT sensors all fall into this category. Each connects through a Network Interface Card providing a unique MAC address and handling physical signaling.

NICs come in various forms. Desktop computers use PCIe cards for Ethernet supporting Gigabit or 10 Gigabit speeds. Laptops integrate wireless adapters for Wi-Fi 6 or 6E standards. Servers often include multiple NICs for redundancy or traffic separation.

The interface configuration includes speed, duplex settings, and VLAN membership. Most modern equipment auto-negotiates these parameters, but manual configuration may be necessary for legacy device compatibility.

Switches, routers, and gateways

Switches connect devices within the same LAN, forwarding data based on MAC addresses to create efficient communication paths. When a frame arrives, the switch examines the destination MAC address and forwards it only to the appropriate port. Switching eliminates unnecessary broadcast traffic by creating direct paths between communicating devices.

Managed switches offer configuration options including VLANs, port security, Quality of Service, and traffic monitoring. Unmanaged switches provide basic Layer 2 connectivity without administrative features. Enterprise environments typically deploy managed switches at all layers for visibility and control.

Routers connect different networks together, directing traffic based on IP addresses. While switching handles local traffic within a broadcast domain, routing moves packets between separate networks. Enterprise routers maintain complex routing tables to determine optimal paths. Layer 3 switches combine switching and routing functions in a single device.

Gateways bridge dissimilar networks, often translating between different protocols. A VoIP gateway might convert between traditional telephone signaling and IP-based voice traffic. Application gateways perform protocol conversion at higher layers.

Cabling and transmission media

Physical cabling carries electrical or optical signals between devices. Category 5e supports Gigabit Ethernet up to 100 meters and remains common in existing installations. Cat 6 handles Gigabit with improved crosstalk rejection and supports 10 Gigabit at shorter distances. Category 6A achieves 10 Gigabit performance across the full 100-meter distance.

Fiber optic cabling uses light pulses instead of electrical signals. Single-mode fiber reaches distances of 10 kilometers or more with laser transmitters. Multi-mode fiber uses LED transmitters and works for distances up to 550 meters depending on speed requirements. Fiber provides immunity to electromagnetic interference and higher security since it doesn’t radiate signals.

Patch panels organize cable terminations in wiring closets, providing a central connection point for structured cabling. Proper cable management includes labeling and documentation. TIA-568 standards define installation requirements for commercial cabling systems.

Network Protocols and Standards That Enable Communication

Ethernet and IEEE standards

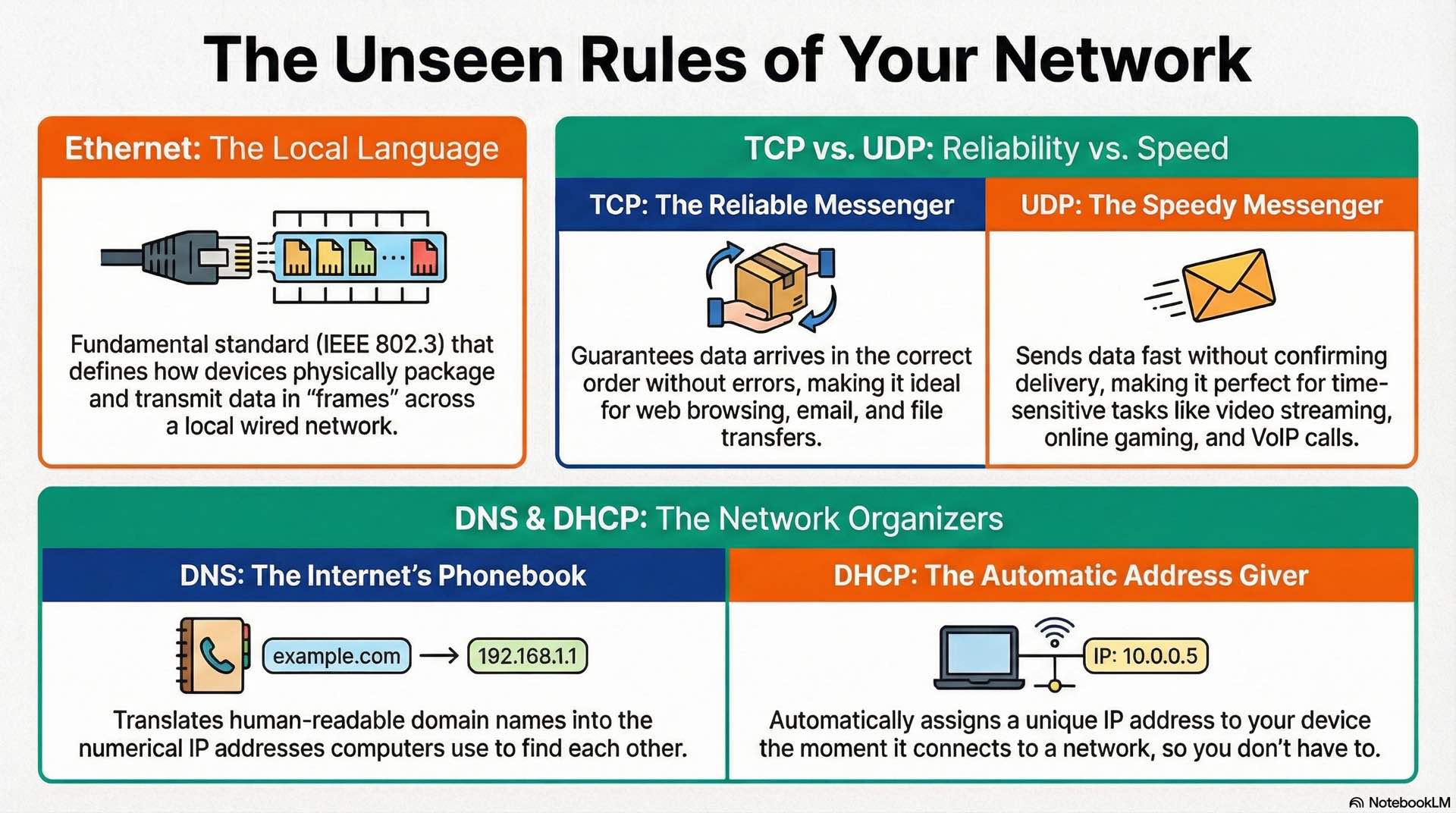

Ethernet protocols defined by IEEE 802.3 dominate wired networking. The standard has evolved from 10 Mbps shared coaxial networks to modern 400 Gigabit point-to-point links. Each speed variant uses specific cable types and signaling methods, but the frame format remains consistent across versions.

An Ethernet frame contains source and destination MAC addresses, a type field indicating the payload protocol, the actual data payload, and a frame check sequence for error detection. Maximum frame size is 1518 bytes for standard frames, with jumbo frames extending to 9000 bytes for high-performance applications.

IEEE 802.1Q defines VLAN tagging, inserting a 4-byte tag between the source MAC address and type field. IEEE 802.1D specifies Spanning Tree Protocol for loop prevention. And IEEE 802.3ad (now 802.1AX) covers link aggregation for combining multiple physical links into a single logical connection.

TCP, UDP, and ICMP protocols

Transport protocols manage data flow between applications. The Transmission Control Protocol provides reliable, ordered delivery of data streams. TCP establishes connections through a three-way handshake, tracks sequence numbers to ensure proper ordering, and retransmits lost segments. Web browsing, email, and file transfers rely on TCP’s guarantees.

User Datagram Protocol offers faster, connectionless transmission without delivery confirmation. UDP sends data immediately without connection setup. VoIP, video streaming, and online gaming use UDP because low latency matters more than occasional packet loss. A dropped packet in a voice call produces a brief gap, but waiting for retransmission would cause noticeable delay.

ICMP handles diagnostic and error messages. The ping utility uses ICMP echo requests and replies to test connectivity. Traceroute sends packets with incrementing Time-to-Live values to map the path between source and destination. ICMP also carries error messages when routers cannot forward packets.

DNS, DHCP, and application protocols

DNS translates human-readable names into IP addresses. When you type a web address, your device queries DNS servers to find the corresponding IP. The hierarchical DNS structure distributes this database globally, with root servers, top-level domain servers, and authoritative nameservers handling different portions of the namespace.

DHCP automates IP address assignment for network devices. DHCP servers maintain address pools and lease configurations to requesting clients. The process involves discovery, offer, request, and acknowledgment messages. Clients periodically renew leases to maintain their addresses.

Application protocols define communication for specific services. HTTP and HTTPS handle web traffic, with HTTPS adding TLS encryption. FTP transfers files between systems. SMTP, IMAP, and POP3 manage email. SNMP monitors network devices and collects performance data.

How IP Addressing and Subnetting Organize Networks

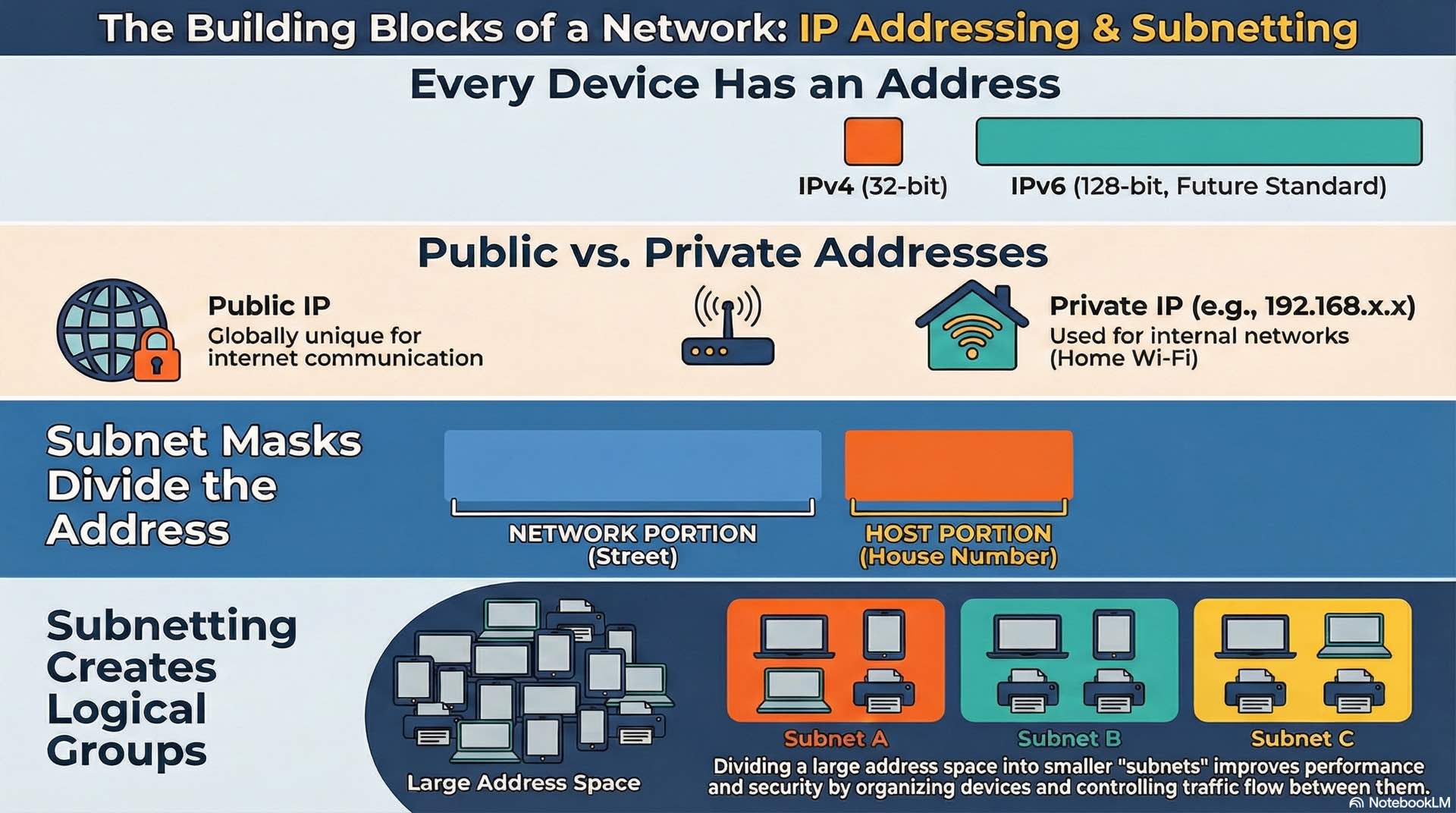

IPv4 and IPv6 addressing models

IPv4 addresses use 32 bits for identification, written as four decimal octets separated by dots. This provides roughly 4.3 billion unique addresses, a number that seemed sufficient in the 1980s but is now exhausted. Network address translation extends IPv4 availability, but the long-term solution is IPv6.

IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses, written as eight groups of four hexadecimal characters separated by colons. This address space is effectively unlimited for practical purposes. IPv6 also simplifies headers for more efficient processing and integrates IPsec security support. Adoption continues gradually, with most networks operating in dual-stack mode supporting both protocols.

Address assignment can be static or dynamic. Servers and infrastructure devices typically use static addresses for consistent accessibility. End-user devices usually receive dynamic addresses through DHCP or its IPv6 equivalents.

Private and public IP ranges

Public IP addresses are globally unique and routable across the internet. Internet service providers allocate public addresses from regional registries. Every organization connecting to the internet needs at least one public address, though NAT allows many internal devices to share a single public address.

Private addresses are reserved for internal use and not routable on the internet. The ranges 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, and 192.168.0.0/16 are designated private in IPv4. Organizations can use these addresses freely within their networks without coordination with external authorities.

NAT translates between private and public addresses at the network boundary. Port Address Translation allows many internal devices to share a single public IP by tracking connections through unique port numbers. This technique has been essential for conserving the limited IPv4 address pool.

Subnet masks and CIDR concepts

Subnet masks divide addresses into network and host portions. A mask of 255.255.255.0 designates the first three octets as network identifier and the final octet for host addresses. This creates a subnet with 254 usable host addresses.

CIDR notation expresses masks using slash format. A /24 network uses 24 bits for the network portion, equivalent to 255.255.255.0. Larger prefix numbers indicate smaller subnets: /25 provides 126 hosts, /26 provides 62 hosts, /27 provides 30 hosts.

Subnetting allows administrators to divide allocated address space efficiently. A company with a /24 public allocation might create multiple /27 subnets for different purposes. Internal networks commonly use private addressing with arbitrary subnetting based on organizational needs.

How Switching and VLANs Control Local Network Traffic

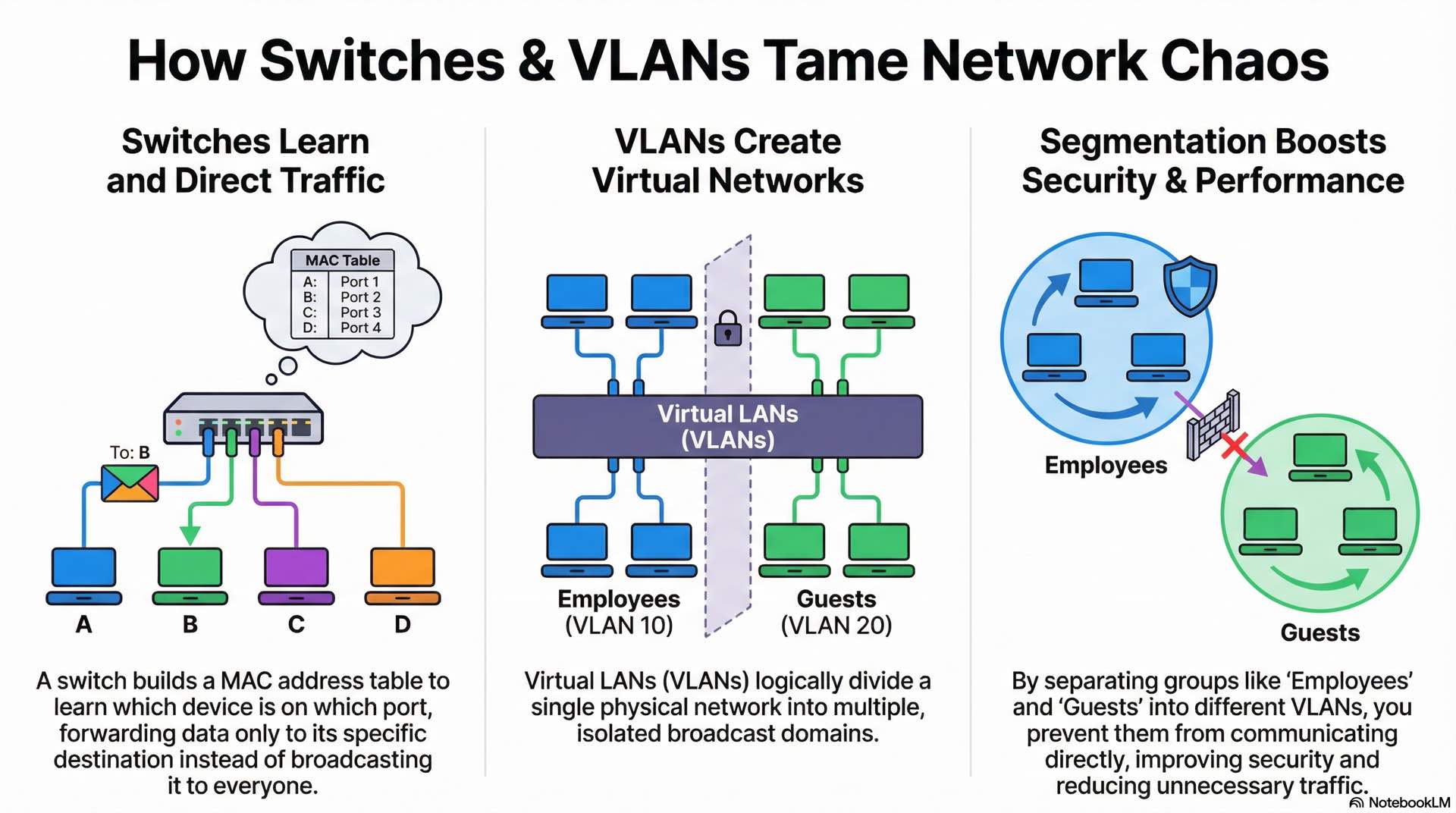

MAC addressing and switching behavior

Every network interface has a unique 48-bit MAC address burned into hardware. The first 24 bits identify the manufacturer, while the remaining 24 bits are a unique serial number. Switches use MAC addresses for forwarding decisions within local network segments.

When a switch receives a frame, it records the source MAC address and port in its MAC address table. This table builds dynamically through traffic observation. For frames with known destination addresses, the switch forwards only to the appropriate port. Unknown destinations trigger flooding to all ports except the source.

MAC address tables have limited capacity and age entries after periods of inactivity. Enterprise switches maintain tables for thousands of addresses. Attacks like MAC flooding can overwhelm these tables, causing the switch to broadcast all traffic.

VLAN creation and network segmentation

VLANs logically segment physical networks into separate broadcast domains. Devices in different VLANs cannot communicate directly even when connected to the same switch. This segmentation improves security and reduces broadcasts.

Administrators assign switch ports to specific VLANs. Access ports belong to a single VLAN and connect end devices. Trunk ports carry traffic for multiple VLANs using 802.1Q tagging. The protocols governing trunk communication ensure frames maintain their VLAN association across interconnected switches.

Common VLAN designs separate user groups by department or security level. A typical configuration might include VLANs for employee workstations, guest wireless, VoIP phones, security cameras, and server infrastructure. Inter-VLAN routing controls communication between segments.

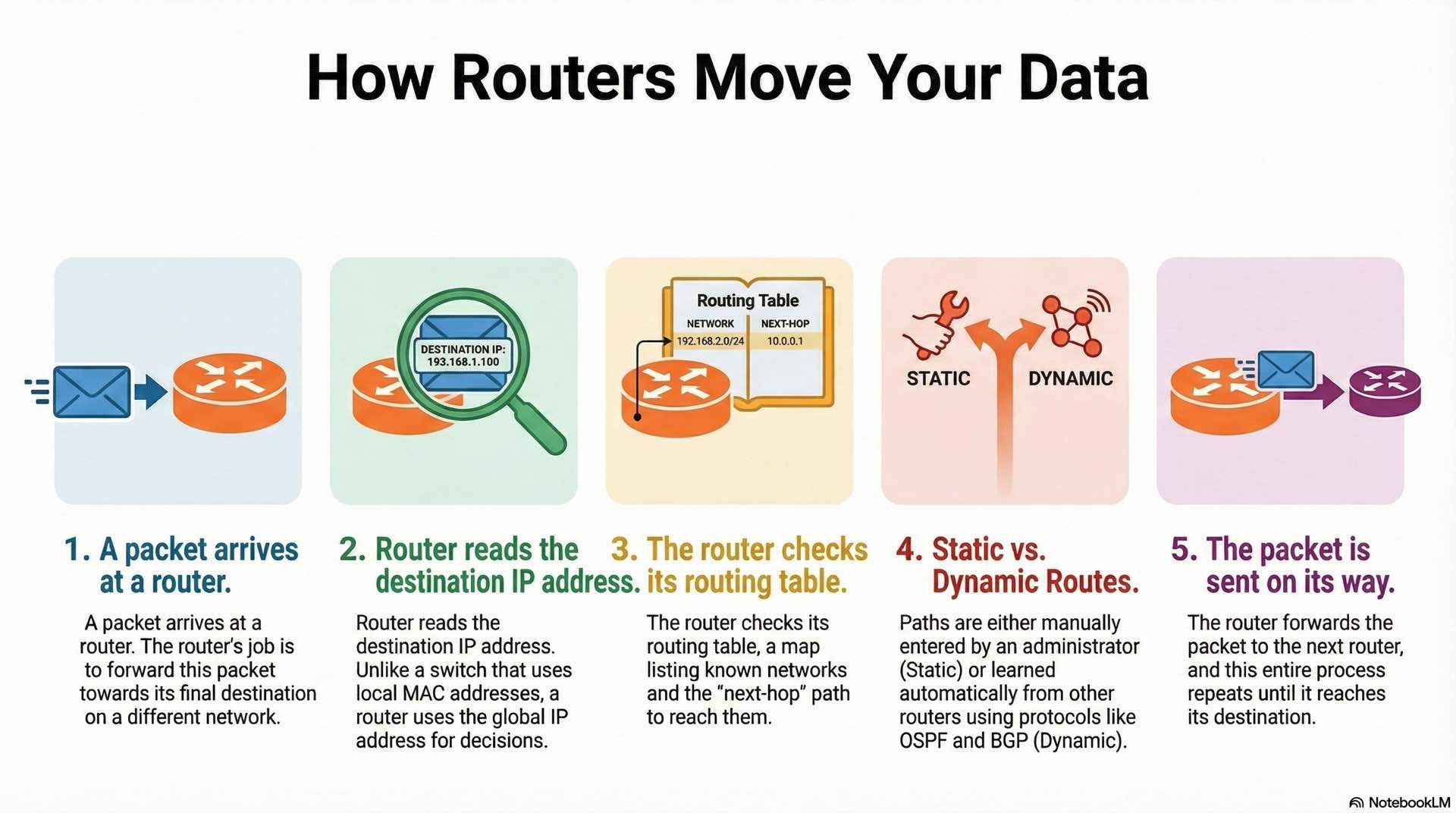

Routing Fundamentals for Moving Data Between Networks

Routing tables and path selection

Routers maintain routing tables that map destination networks to next-hop addresses and outgoing interfaces. When a packet arrives, the router examines the destination IP address and consults the table to determine where to forward it. Unlike switching, which operates on MAC addresses within a single broadcast domain, routing uses IP addresses to forward packets across network boundaries. The most specific matching route wins when multiple entries could apply.

Each routing table entry includes the destination network, subnet mask, and next-hop address. A metric indicates the route’s desirability. Administrative distance values prioritize routes learned from different sources when multiple paths exist to the same destination.

Routing decisions happen independently at each hop. A packet from New York to Tokyo might traverse a dozen routers, each making its own forwarding decision based on local routing information. This distributed approach provides resilience when individual paths fail.

Static and dynamic routing methods

Static routes are manually configured by administrators. This approach provides complete control and predictability but doesn’t adapt to topology changes. Small networks use static routing exclusively. Larger networks use static routes for specific purposes like default gateways or policy-based path selection.

Dynamic routing protocols automate route discovery and selection. Interior gateway protocols like OSPF calculate optimal paths based on link costs. Exterior gateway protocols like BGP handle routing between autonomous systems, forming the backbone of internet connectivity.

OSPF uses link-state algorithms for shortest path calculation where routers share complete topology information. BGP uses path-vector algorithms focused on policy rather than pure optimization. RIP, an older distance-vector protocol, remains in use for simple networks.

Wireless Networking Basics and Wi-Fi Communication Principles

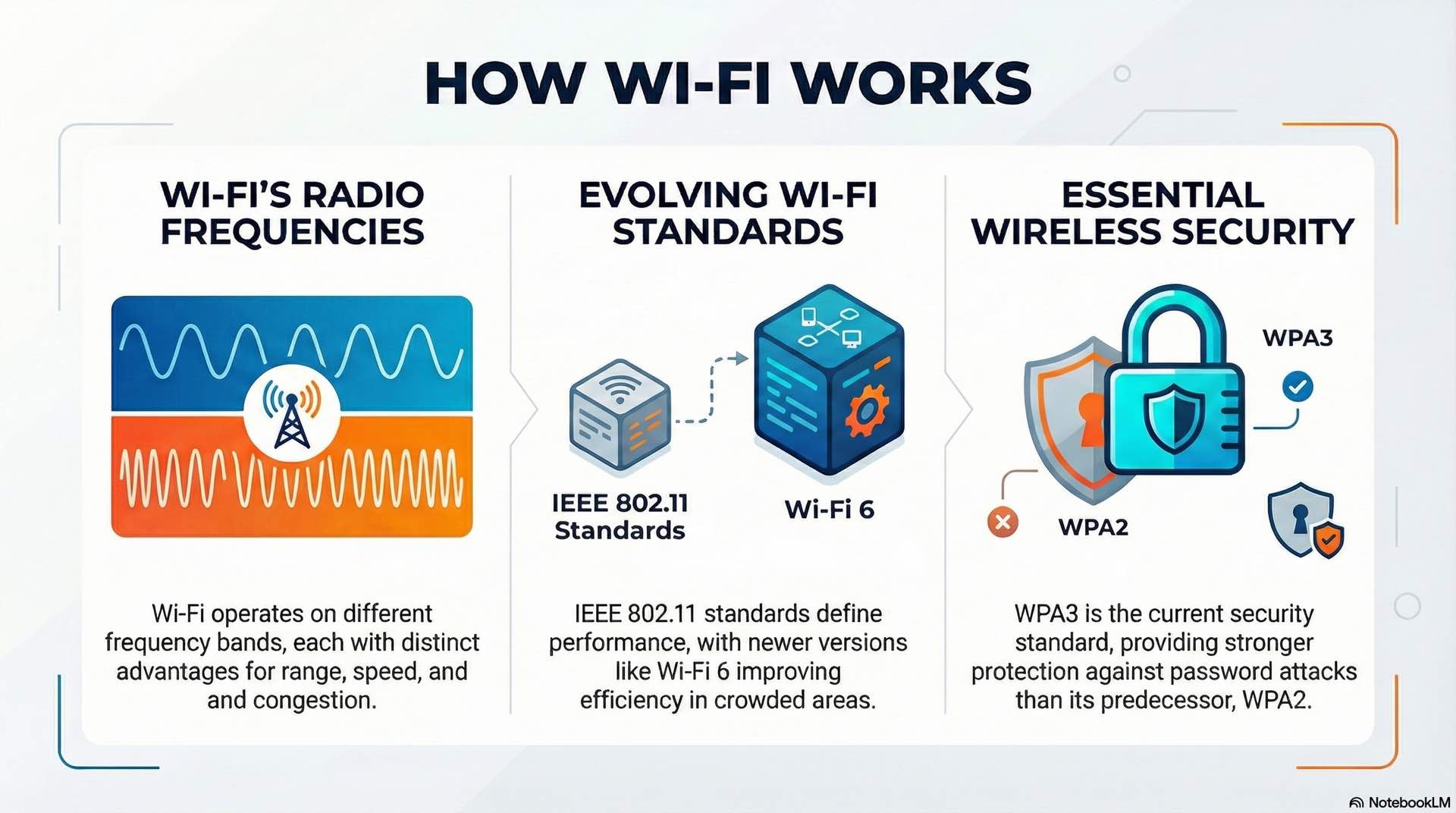

Wi-Fi frequency bands and standards

Wi-Fi operates in unlicensed spectrum bands at 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz. The 2.4 GHz band offers better range and wall penetration but suffers from congestion and interference from Bluetooth devices, microwaves, and neighboring networks. The 5 GHz band provides more channels and higher throughput but shorter range. The 6 GHz band, available with Wi-Fi 6E, adds substantial spectrum for future growth.

IEEE 802.11 standards define wireless capabilities. Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) supports multi-gigabit speeds using wide channels up to 160 MHz. Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax) improves efficiency in high-density environments through OFDMA technology. And Wi-Fi 6E extends these capabilities into the 6 GHz band.

Access points broadcast SSIDs to identify available networks. Channel selection avoids overlap with neighbors to minimize interference. Professional deployments use site surveys to plan coverage patterns and optimize signal distribution.

Wireless security and coverage concepts

WPA3 represents the current security standard for Wi-Fi networks. It replaces the vulnerable WPA2-PSK with Simultaneous Authentication of Equals, providing stronger protection against password-guessing attacks. Enterprise environments use 802.1X authentication with RADIUS servers for individual user credentials.

Coverage design considers signal propagation, user density, and application requirements. High-density venues require more access points operating at lower power to serve concentrated users. Open office areas might use fewer, higher-power access points.

Controller-based architectures centralize wireless management across multiple access points. Standalone deployments suit smaller environments. Cloud-managed solutions offer remote administration without on-premises hardware.

Network Security Basics for Traffic Protection

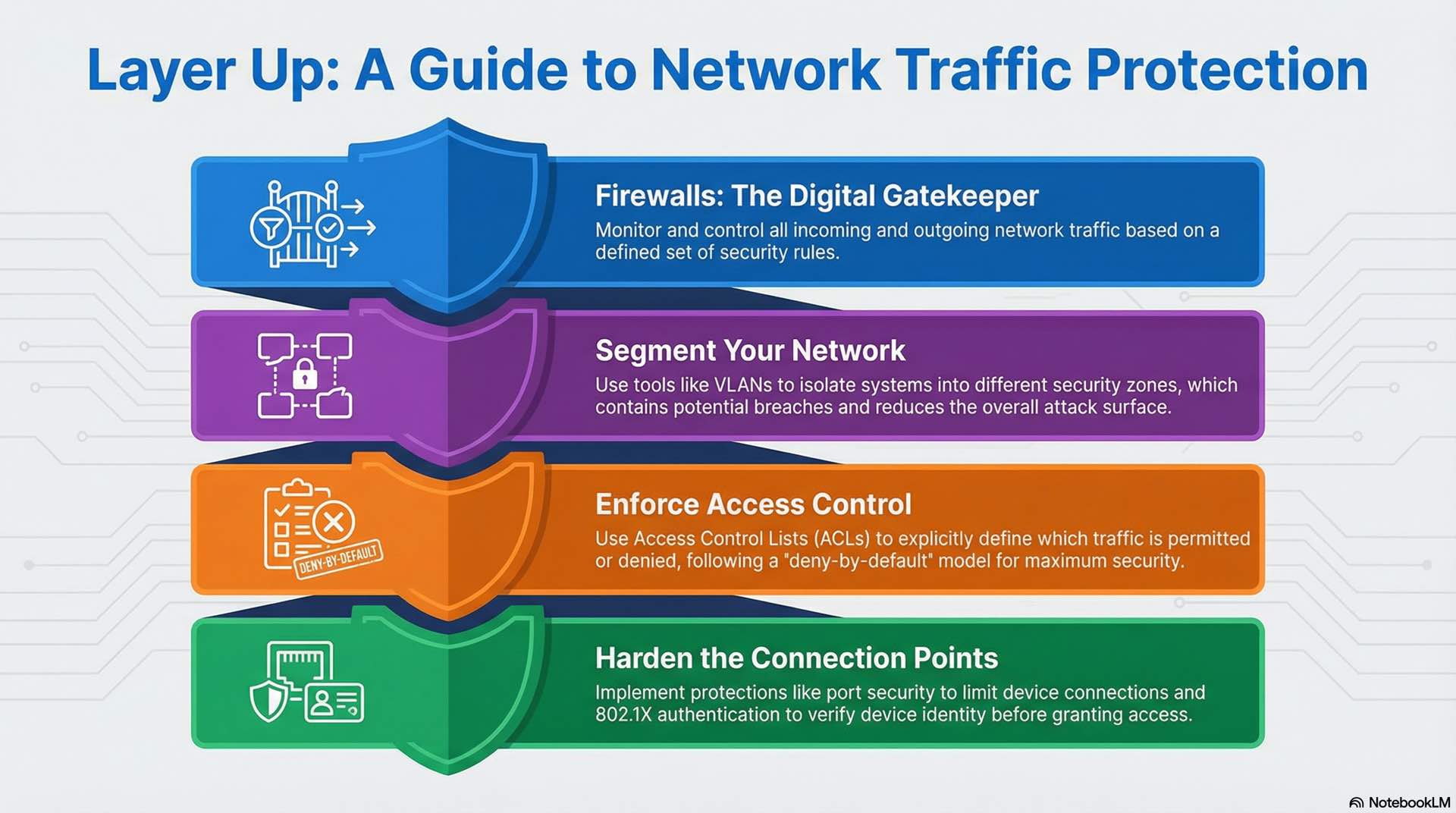

Firewalls and access control principles

Firewalls monitor and control traffic based on defined security rules. Packet-filtering firewalls examine header information like source and destination addresses and ports. Stateful inspection tracks connection states to make more informed decisions. Next-generation firewalls add application awareness and threat detection capabilities.

Access control lists specify which traffic is permitted or denied at router and switch interfaces. Rules typically follow a deny-by-default security model where only explicitly allowed traffic passes. ACL design requires careful ordering since rules are processed sequentially.

Defense-in-depth strategies layer multiple controls. Perimeter firewalls protect internet boundaries. Internal segmentation limits lateral movement. Host-based firewalls provide final protection at individual devices.

Segmentation and basic protection methods

Network segmentation isolates systems into security zones with controlled interconnection points. Critical infrastructure occupies protected segments with strict access policies. Guest networks exist in separate zones with limited internal access. This approach contains breaches and reduces attack surface.

VLANs provide Layer 2 segmentation, but traffic between VLANs requires firewall inspection for true security control. Private VLANs restrict communication within segments. Microsegmentation extends these concepts to individual workloads.

Additional protections include port security to limit MAC addresses, DHCP snooping to prevent rogue servers, dynamic ARP inspection blocks spoofing attacks, and 802.1X authentication verifies device identity before granting access.

Network Monitoring and Troubleshooting Methods

Traffic analysis and performance metrics

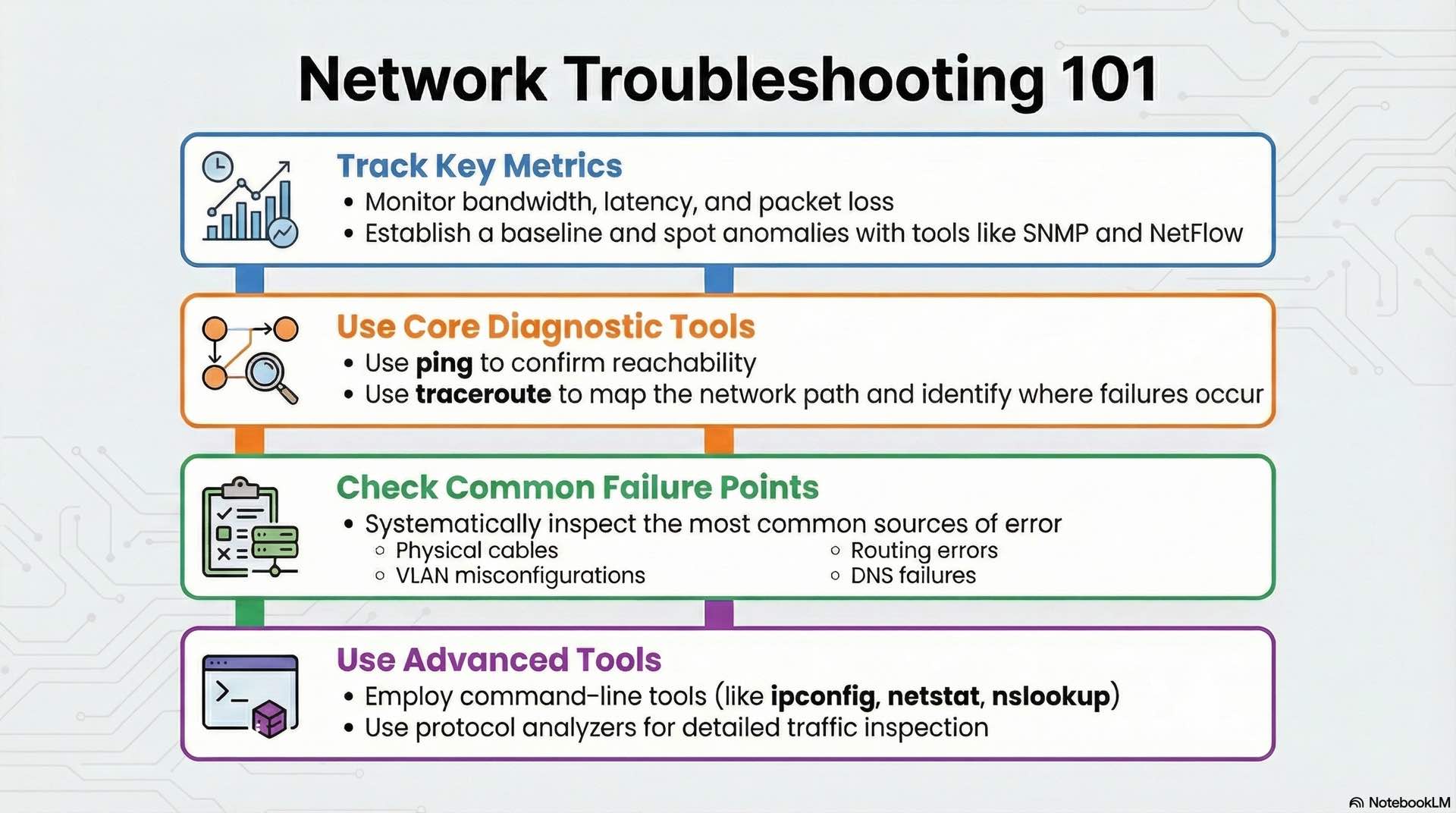

Network monitoring provides visibility into traffic patterns and utilization anomalies. SNMP polling collects interface statistics like bytes transferred, errors, and discards. NetFlow and similar technologies capture traffic metadata for analysis. Monitoring covers both switching infrastructure at Layer 2 and routing devices at Layer 3.

Key metrics include bandwidth utilization, latency, and packet loss. Baseline measurements establish normal operating ranges. Alerts trigger when metrics exceed thresholds, enabling proactive problem identification. Switching metrics like port utilization and MAC table size complement routing metrics like CPU load and route table stability.

Traffic analysis reveals application behavior, identifies top talkers consuming bandwidth, and detects unusual patterns that might indicate security incidents. Long-term trending supports capacity planning and justifies infrastructure investments.

Common network faults and diagnostic tools

Troubleshooting starts with basic connectivity verification using ping and traceroute. Ping confirms reachability and measures latency. Traceroute reveals the path packets take and identifies where failures occur.

Common faults include cable problems and duplex mismatches, VLAN misconfiguration, routing errors, and DNS failures. Systematic troubleshooting follows the OSI model, checking physical connectivity before examining higher-layer issues.

Command-line tools like ipconfig, netstat, and nslookup provide diagnostic information on Windows systems. Linux equivalents include ifconfig, ss, and dig. Protocol analyzers capture and decode traffic for detailed inspection.

Effective troubleshooting requires understanding how protocols interact across network layers. A web page that won’t load might result from DNS resolution failures, routing problems, firewall blocks, or server-side issues. Isolating the fault layer focuses investigation efficiently.

Documentation supports troubleshooting with baseline records and network topology diagrams. Change management processes track modifications that might cause problems. Configuration backups enable rapid recovery when changes cause failures.

Building reliable connectivity requires mastering how network infrastructure supports business operations at every layer. The protocols that govern data transmission ensure consistent communication between diverse systems. Understanding switching behavior within local segments enables efficient traffic handling, while routing determines paths across interconnected networks for end-to-end delivery. These fundamentals remain constant whether managing a small office LAN or enterprise infrastructure spanning multiple continents.