A clear overview of network fundamentals for modern networks, covering core concepts, components and IP addressing essentials.

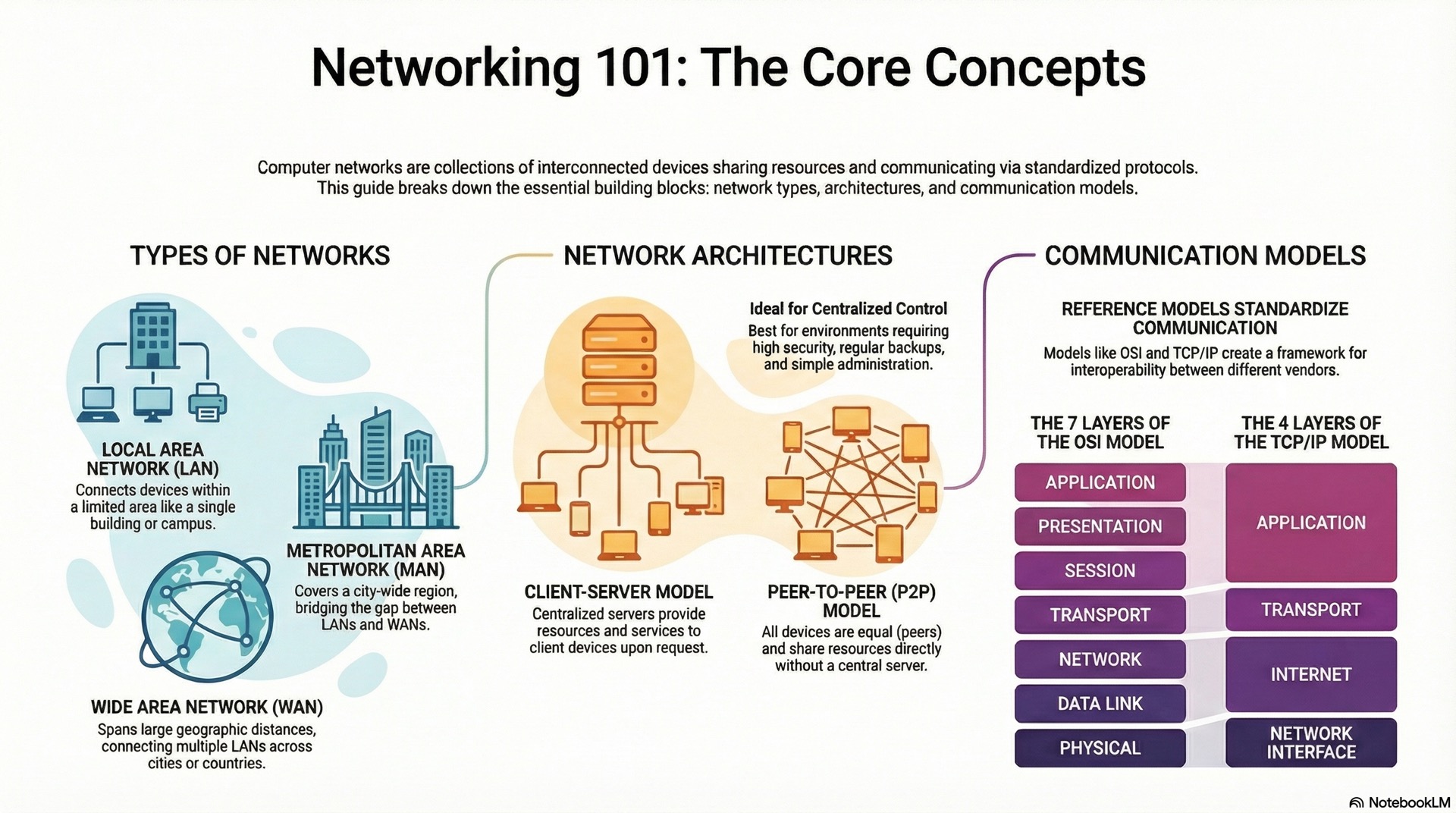

Understanding network fundamentals and network basics starts with recognizing how devices connect and exchange information. Modern IP addressing systems enable reliable communication between computers, servers and mobile devices. These network fundamentals create the foundation for digital connectivity across local and wide-area environments. You’ll learn how LANs differ from WANs, how client-server models organize resources and how layered reference models standardize communication. Each concept builds on core network basics that IT teams use daily.

Introduction to Networking Concepts

What a Network Is and Why It Matters

A network is a collection of interconnected devices that share resources and communicate through standardized protocols. Organizations use network fundamentals to enable collaboration, centralize data storage and provide secure access to applications. Networks range from small office setups to global infrastructures spanning continents. Without proper networks, modern business operations and cloud services would not function. Understanding network fundamentals helps IT teams design systems. This ensures they meet performance and security requirements. These principles apply across industries from education to healthcare.

Basic Components of a Network

Every network includes endpoints, transmission media and intermediary devices that manage traffic flow. Endpoints are devices like computers, printers and smartphones that send or receive data. Transmission media include Ethernet cables, fiber optics and wireless radio frequencies. These carry signals between devices across different distances. Routers, switches and access points act as intermediary devices. They direct traffic, filter packets and extend coverage. Network interface cards (NICs) handle the physical connection and protocol translation. Power over Ethernet (PoE) switches supply electricity while transmitting data. These components implement network basics in modern environments.

How Devices Communicate and Share Data

Devices send data as small packets across the network. Each packet includes source and destination addresses plus error-checking codes. Switches read MAC addresses to forward frames within local segments. Routers examine IP addressing information to route packets between networks. Protocols like TCP ensure reliable delivery by confirming receipt. When a user accesses a shared folder, the client requests specific files. The server validates permissions and sends data back through switches. This process demonstrates how network fundamentals enable resource sharing through proper IP addressing implementation.

LAN, WAN and MAN Definitions

Local Area Networks (LAN) and Typical Use Cases

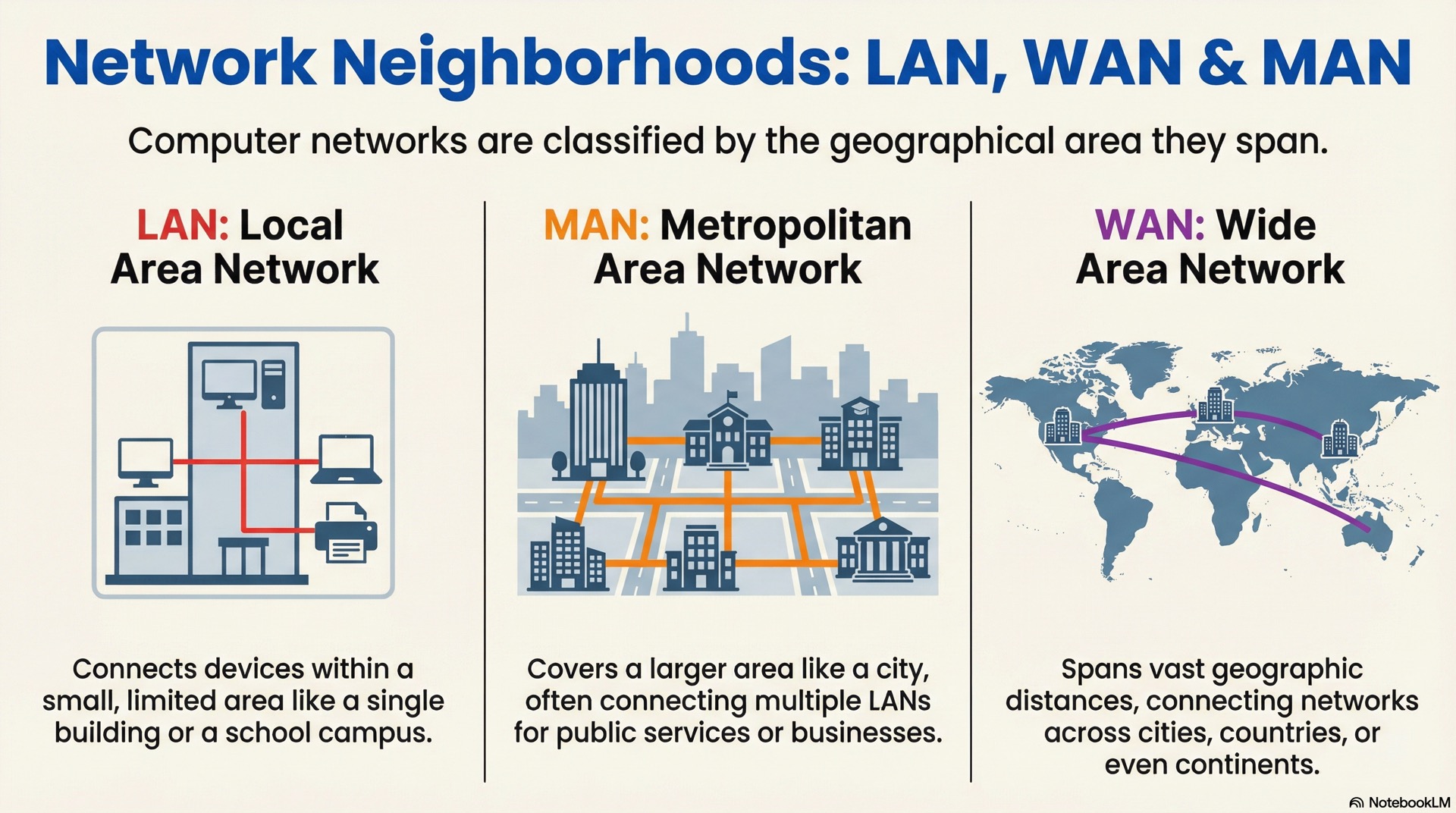

A LAN connects devices within a limited area like a building or campus. Businesses deploy LANs to link workstations, printers and servers at high speeds. Ethernet LANs typically operate at 1 Gbps, 2.5 Gbps or 10 Gbps. Wireless LANs use Wi-Fi standards like 802.11ac or 802.11ax. LANs provide centralized file storage and shared internet access. Schools use network fundamentals to connect classrooms, libraries and offices through LAN infrastructure. Manufacturing facilities integrate production equipment with inventory systems. These local networks support daily operations for most organizations.

Wide Area Networks (WAN) and Long-Distance Connectivity

A WAN spans large geographic distances and connects multiple LANs. ISPs build WANs using fiber-optic backbones, satellite links and leased circuits. Organizations purchase WAN services to link branch offices. Remote workers access centralized databases through WAN connections. Technologies include MPLS, SD-WAN and dedicated circuits. Latency and bandwidth costs increase with distance. Network architects apply network fundamentals to optimize routing and balance performance with expense. Banks synchronize transaction records between data centers using WANs. Understanding WAN principles is essential, and these network fundamentals support large-scale connectivity.

Metropolitan Area Networks (MAN) and Regional Deployments

A MAN covers a city or metropolitan region. It bridges the gap between LANs and WANs in scope. Municipal governments deploy MANs to connect public services and emergency centers. Cable providers use MAN infrastructure to distribute broadband internet. MANs typically operate at 10 Gbps to 100 Gbps over 5 to 50 kilometers. Universities with multiple campuses build MANs to share resources and apply network basics across locations. They reduce reliance on long-distance circuits while maintaining high performance. These regional networks extend services across cities and campuses.

Client-Server and Peer-to-Peer Models

How Client-Server Models Organize Resources

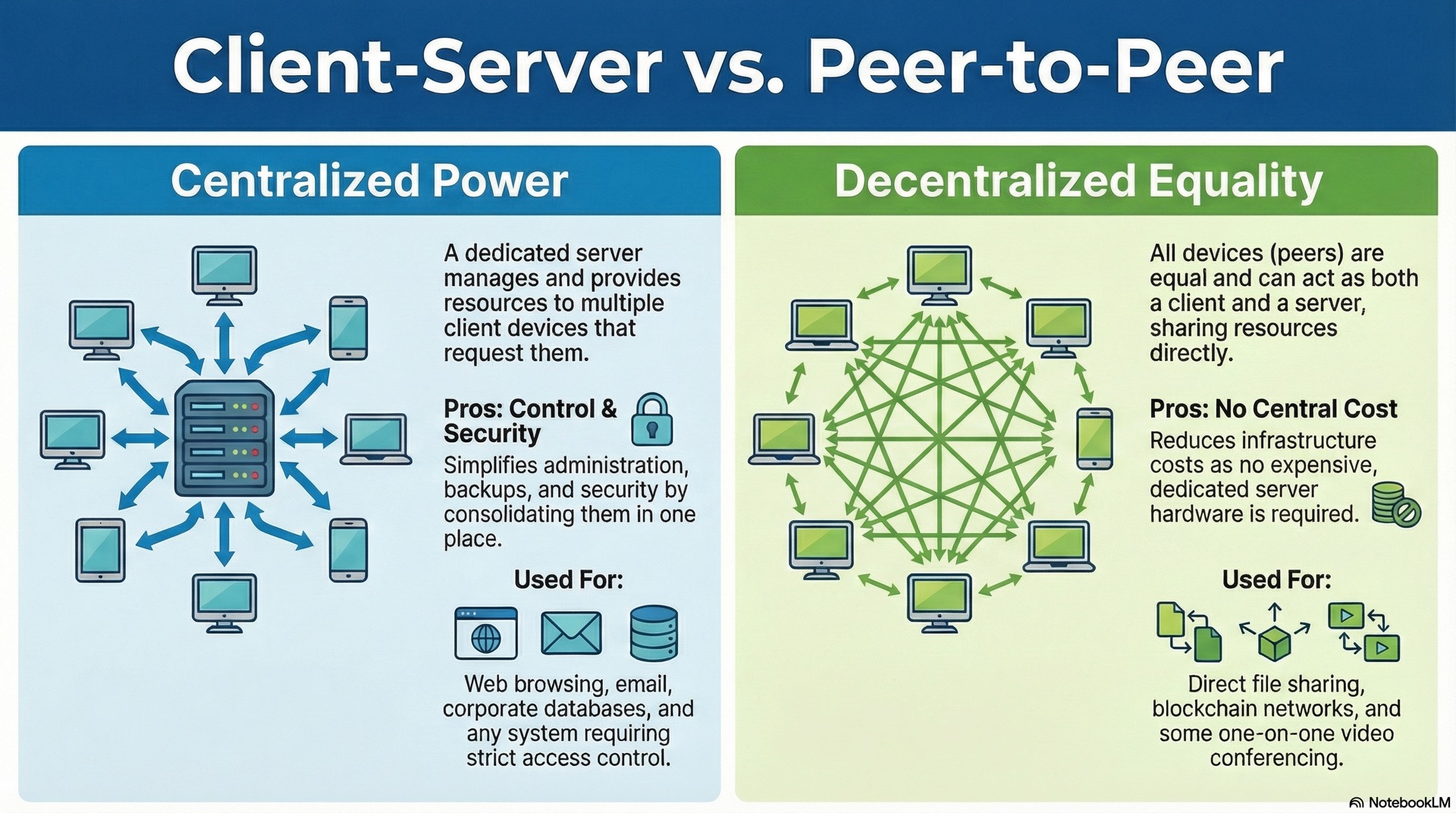

The client-server model centralizes data and services on dedicated servers. Servers run specialized software to manage databases and host websites. Clients initiate connections and display results to users. This architecture simplifies administration by consolidating security policies and backups. Web browsing relies on client-server communication between browsers and servers. Enterprise applications use three-tier designs with separate presentation and logic layers. Understanding these models is essential for network fundamentals planning. Centralized control improves security but requires robust hardware. Network basics guide the implementation of client-server architectures across organizations.

Peer-to-Peer Communication and When It’s Used

Peer-to-peer (P2P) networks distribute responsibilities across all connected devices. Each peer acts as both client and server. They share files or processing power directly with other peers. Small offices use P2P file sharing for quick document exchange. P2P models reduce infrastructure costs because no dedicated servers are required. Blockchain networks operate on P2P principles with distributed validation. However, P2P systems lack centralized backup and consistent security enforcement. These networks represent an alternative approach compared to traditional architectures.

Key Differences and Practical Applications

Client-server models excel in environments requiring strict access control and monitoring. Hospitals deploy them to manage electronic health records with audit trails. P2P models suit scenarios where resource sharing is informal. Video conferencing platforms use P2P for direct calls. Hybrid approaches combine both models for authentication and data transfer. Understanding these differences helps designers choose appropriate architectures based on network fundamentals. Proper selection depends on scalability and security needs. Each model addresses different aspects of network basics in practice.

Physical, Data Link and Layers

Role of the Physical Layer in Transmission

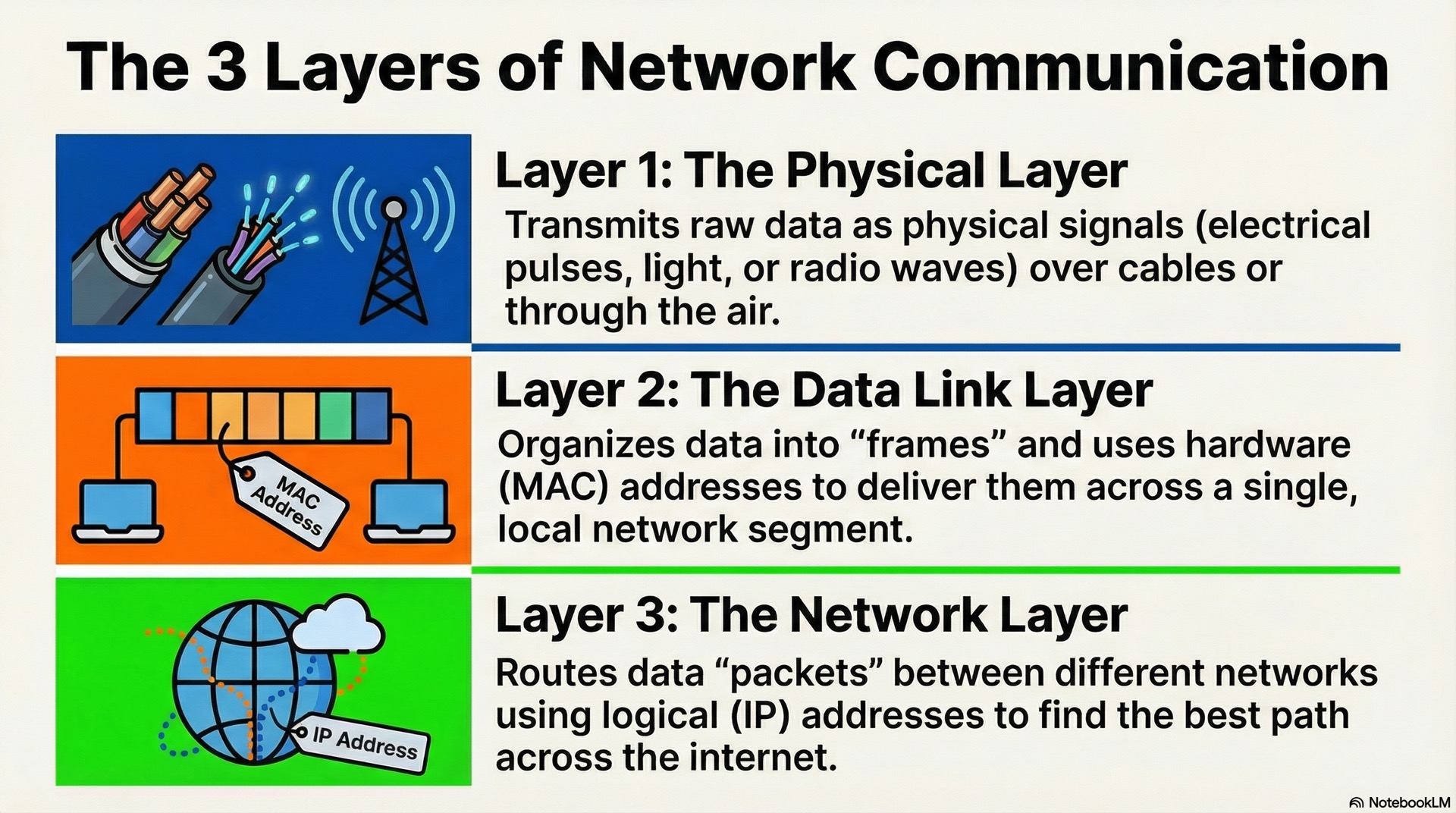

The Physical layer defines electrical and optical specifications for transmitting bitstreams. Ethernet cables use copper wires with voltage changes. Fiber-optic cables transmit light pulses through glass strands at speeds exceeding 100 Gbps. Wireless networks modulate radio frequencies to carry digital signals. Physical layer standards specify connector types, cable lengths and transmission speeds. Network interface cards convert digital data into physical signals. Distance limitations and electromagnetic interference affect performance. This layer provides the foundation for all core network functions.

How the Data Link Layer Structures Frames

The Data Link layer organizes bitstreams into frames. It adds error detection and manages access to shared media. Frames include header fields with MAC addresses and error-checking codes. Switches operate at this layer by reading MAC addresses. They forward frames only to intended recipients. Ethernet uses CSMA/CD to prevent simultaneous transmissions. Wi-Fi access points employ CSMA/CA to coordinate wireless transmissions. The Data Link layer ensures reliable delivery over single segments. This prepares data for routing based on IP addressing principles covered in network fundamentals.

How the Network Layer Handles IP Addressing and Routing

The Network layer manages IP addressing, packet forwarding and path selection. IPv4 addresses use 32-bit values in dotted-decimal notation. IPv6 addresses extend to 128 bits for vast address spaces. Routers examine destination addresses and choose optimal paths. They use routing protocols like OSPF or BGP. Subnetting divides address ranges into smaller segments for control. Network Address Translation allows private addresses to share public connections. Packet fragmentation occurs when data exceeds MTU sizes. This layer implements the core IP addressing logic for internetworks. Understanding IP addressing is critical because it enables device identification. Proper configuration ensures network systems function correctly across all connected infrastructure.

OSI and TCP/IP Models Overview

Purpose of Reference Models in Networking

Reference models provide standardized frameworks for protocol interaction. The OSI model and TCP/IP modelorganize functions into logical layers. Each layer has specific responsibilities for data handling. Engineers use these models to troubleshoot connectivity problems. Standardization enables equipment from different vendors to interoperate. All devices follow the same layered specifications. Network certifications test knowledge of these frameworks and network fundamentals. They ensure technicians understand fundamental protocol relationships and network basics. These models are essential components of network education. Reference models guide both troubleshooting and design processes.

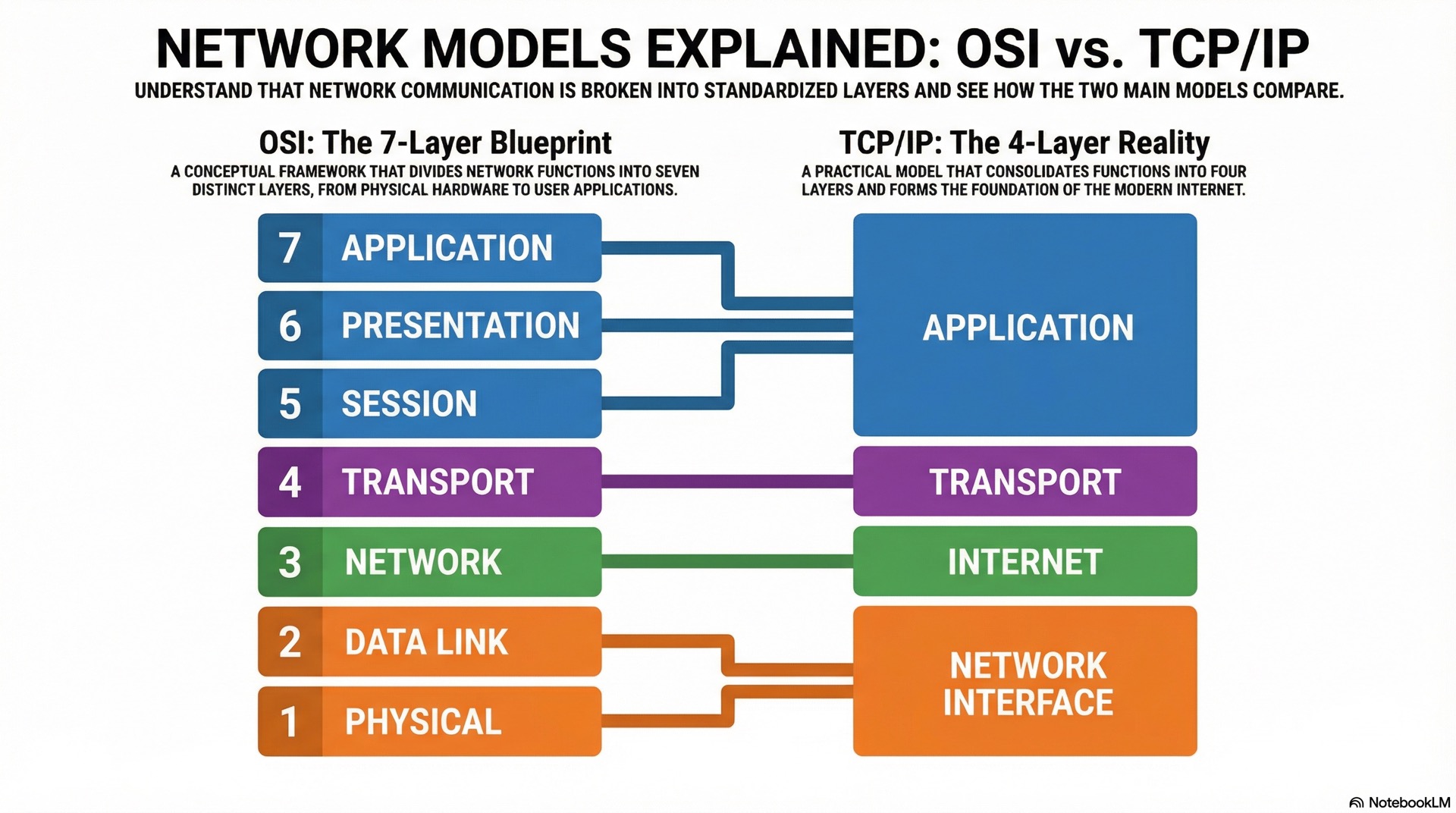

OSI Model Layers at a Glance

The OSI model divides networking into seven layers. Physical and Data Link layers handle hardware transmission. Network and Transport layers manage IP addressing and routing. Session, Presentation and Application layers coordinate dialog control and formatting. Each layer communicates only with adjacent layers. This creates modular boundaries that simplify design. Firewalls filter traffic at multiple OSI layers. They inspect both addresses and application payloads. Understanding all seven layers helps diagnose performance bottlenecks. IT professionals use this layered approach when designing and troubleshooting networks.

TCP/IP Model Structure and Real-World Alignment

The TCP/IP model consolidates OSI layers into four practical layers. Network Interface combines Physical and Data Link functions. The Internet layer implements IP routing and addressing. Transport layer protocols like TCP provide reliable delivery. Application layer protocols such as HTTP interface with user software. Most modern networks implement TCP/IP protocols. These standards emerged from real-world internet deployments. Network engineers map TCP/IP behavior onto OSI layers. This alignment helps when analyzing protocol interactions and network basics. The TCP/IP model reflects how networks operate in real operational settings.

Modern networks depend on structured network fundamentals that define device connectivity and traffic routing. Understanding network basics like LAN and WAN architectures enables proper system design. Client-server models and layered reference frameworks support scalable networks. Mastering IP addressing principles ensures reliable connectivity across platforms. Physical, Data Link and Network layers collaborate to move data efficiently. These network fundamentals provide the foundation for advanced topics. Network security, quality of service and software-defined networking build on these core network basics. IT teams apply IP addressing and routing concepts daily when implementing network fundamentals in real-world deployments.